|

|

Geohistory

five

centuries of geological research in the Apuan Alps

|

|

|

The morphological rarity of the Apuan Alps has always

been an attraction for naturalists-travellers, or at least, it has been so

since the 16th century, when a scientific investigation on the mountain

range was carried out to understand its nature and find natural products

useful for economy.

In the modern age famous geologists used to match

excursions with the pleasure of naturalistic knowledge. Famous is

the excursion by Andrea Cesalpino (1525-1603), who focused on a firestone

"stone by ovens",

described as “invincible to fire”, found in Cardoso di Stazzema.

|

|

|

|

In the 17th

century the bohemian Daniel Meisner (1585-1625) and the dutch Jan Jansson (1588-1664) visited the area and drew the

valley of Seravezza, pinpointing the sites for marble

excavation and silver extraction.

The Apuan Alps, visible from western Florence, were particularly fascinating

for its citizens, who grew up surrounded by Renaissance culture and,

therefore, naturally inclined to discover nature from an aesthetic and

scientific point of view.

|

|

|

%20et%20alii,%20Thesaurus%20philo-politicus…,%20Francoforte%201629.jpg)

Daniel Meisner

(1629): Apuan Alps as natural space of the aesthetic and scientific

discovery of the nature

|

|

|

The visits were already numerous in the 18th century. In those

years, several naturalists showed their

growing interest in the Apuan Alps which had become a privileged research

field for hydrogeological studies and geo-mineral research in Italy.

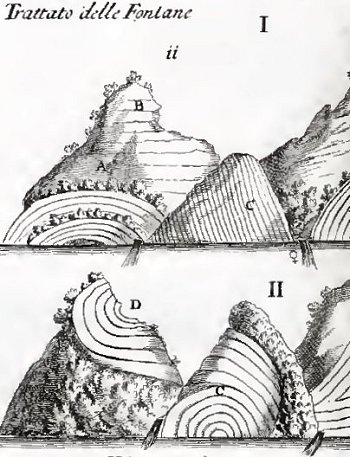

Here,

Antonio Vallisnieri senior (1661-1730) developed and tested the new

theory on the underground water cycle (1704-1715), thanks to the close

relation between water springs and karst cavities.

Meanwhile, explorations

of mines and studies on mineralization took off, with the active

participation, among others, of Giovanni Arduino (1714-1795) and Lazzaro

Spallanzani (1729-1799).

As a result, the first geological descriptions of

the Apuan Alps was produced, based on Arduino’s chronostratigraphic approach

and pointing out the ancient core of the mountain range consisting of schist

“primitive rocks” covered by “secondary rocks”. moreover, the description of the naturalistic voyage of Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti

(1712-1783) in 1743 is rich in content as he described not only Apuan rocks

and minerals, but also physical landforms and morphogenetic agents.

Antonio

Vallisneri

(1714):

on the origin of

springs, based on an exploration in the Apuan Alps and Apennines

click on image to

start movie

(created by Marco Yais) |

|

|

|

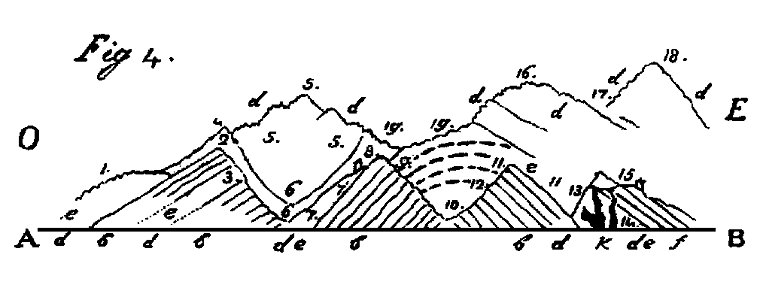

Paolo Savi

(1833): "cut" of the Apuan Alps (cross-section for a first

'plutonist' interpretation of the apuan elipsoid)

|

|

|

In 1833, for the first time the Apuan Alps are shown in a geological

cross-section in a work by Paolo Savi (1798-1871) who gives a ‘Plutonic’

interpretation of the mountain range. According to him, it was raised by the

intrusion of a deep magma body and became a remnant of an ancient orographic

ridge – called “metalliferous chain” – originally situated in the area from

La Spezia to Mt. Argentario.

For almost half a century, literature on geology was dominated by the

scientific contributions of Italian and foreign geologists (Coquand, Pareto,

Puggard, Simi, Cocchi, De Stefani) who used to support the well-established

theory of the Apuan Alps as a single anticline of Plutonic origin. Research

is, nevertheless, rich in surprises and important discoveries. In 1872,

Antonio Stoppani (1824-1891) and Igino Cocchi (1827-1913) in two different

studies found the first morainic deposits in the Apuan Alps and presented

them to the scientific community as the first Apennine marks of the

Quaternary Glaciations.

|

|

|

|

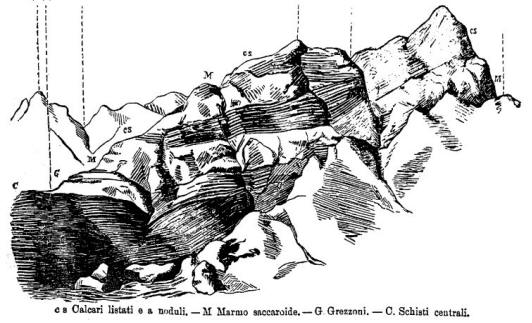

Modern geology began with a systematic survey of the Apuan Alps completed

between 1879 and 1890 by Bernardino Lotti (1847-1933) and Domenico Zaccagna

(1851-1940). The two engineers of the Geological Royal Committee belonged to

the ‘autochthonist’ school of thought assigning the Apuan rocks to a single

stratigraphic sequence excluding any possibility of nappe overlapping.

Therefore, they proposed a folding tectonics characterized by regular folds

with double vergence without dealing with the existence of faults.

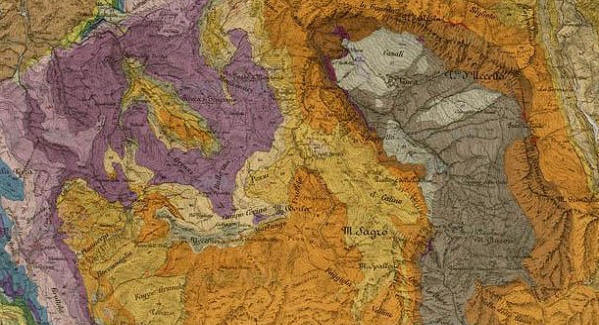

Domenico

Zaccagna

(1881): Mt. Sagro natural section |

|

|

The map

drawing was completed by Domenico Zaccagna alone, who retrieved and developed the

contemporary studies by Igino Cocchi (1827-1913) and Carlo De Stefani

(1850-1924), in compliance with the geological survey project presented at

the Second International Congress in Bologna in 1881. These are the first

examples of modern geological cartography in Italy.

|

|

|

|

The scientific commitment was matched with the institutional interest of the

Geological Committee, which aimed at providing the Apuan marble mining industry with an

useful instrument in a historic moment of remarkable spreading of quarrying

activities beyond the traditional basins of Carrara, Massa and the area of

Versilia.

In 1917, despite their sheer ‘autochthonist’ approach, the Zaccagna and

Lotti’s geological map enabled, Stanislaw Lencewicz (1889-1944) to

reinterpret the structure of the mountain range from an ‘allochthonist’

perspective, showing the tectonic duplication of the Tuscan sequence.

|

|

|

Domenico

Zaccagna

(1880-1886): Mt. Sagro's geological map - scale 1:25.000 |

|

|

|

For the very first time in

the history of the Apuan Alps and Apennines the allochthonous origin of nappes was recognized, though it had already been

proposed by Lugeon and Argand for the Pennine Alps (1905) on the basis of

the overthrusting of two equivalent stratigraphic sequences. In the

following two decades the geological studies, especially by experts from the

central European school and culture, enabled the identification of a

‘tectonic window’ in the central part of the Apuan range. In particular, in

1926, Norbert Tillman (1883-1947) described the Apuan Alps as a complex

structure of folded sedimentary sequences which are overturned, faulted and

tectonically overlapped. After the Second World War the main subject of

geological studies was the gravitational sliding of nappes, which led Carlo

Migliorini (1891-1953) to formulate the theory of ‘composite wedges’ (1948),

according to which nappes may gradually slip for hundreds of kilometres

through different and subsequent phases thanks to a limited number of

inclined surfaces. The interpretation was then retrieved and developed by

Giovanni Merla (1906-1983) and Livio Trevisan (1909-1996), who, shortly

afterwards, described a gravitational sliding of nappes progressively moving

from the Tyrrhenian to the Adriatic area thanks to the upthrust of

subsequent tectonic ‘ridges’ or ‘wrinkles’. In the same period, Felice

Ippolito (1915-1997) carried out geological-petrographic studies on the

Apuan Alps and Pisani Mountains assigning the Apuan rocks to three

superposed sequences. The ‘Autochthonous’ sequence is the deepest one and is

overthrusted by an equivalent lithological sequence, called ‘Tuscan Nappe’

which is in turn topped by the ‘Ligurian Unit’.

|

|

|

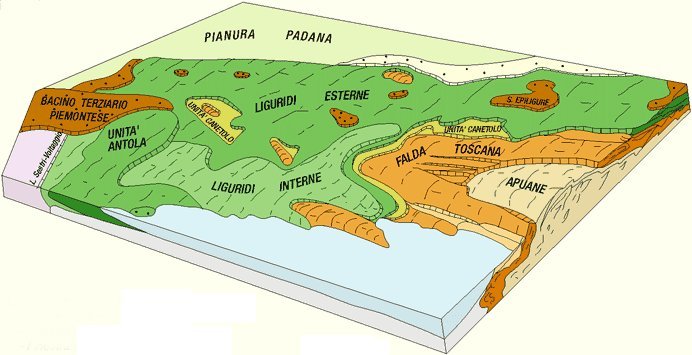

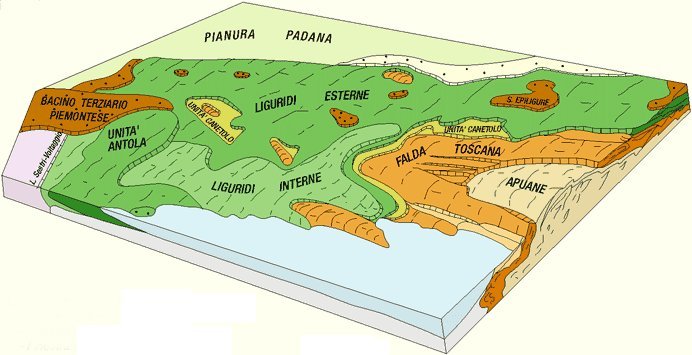

Piero Elter

(1974): Northern Apennines diagram block

|

|

|

In the 1960’s the Apuan Autochthon is described, especially by Enzo Giannini

(1919-1992), as the most remarkable part of a structural high (geoanticline)

which divides the two main basins, the ‘inland’ (eugeosyncline) and the

‘outer’ one (miogeosyncline). The Apuan tectonic ridge was allegedly

overthrusted by the Tuscan and Ligurian units because of tangential pushes

by the oceanic area towards the foreland, thus leading to the late formation

of rigid structures such as horsts (Apuan) and grabens (Serchio

Valley).

The quality leap in the interpretation of the evolution of the Apuan Alps

and Northern Apennines was made thanks to the theoretical support of ‘plate

tectonics’ or ‘global tectonics’ with the identification of the physical

“engine” able to provide the necessary push for large translations of nappes.

After 1975, a series of studies on the geometry of polyphase deformations,

created by the superposition of different tectonic phases, took place within

a framework consistent with the Cenozoic paleographic evolution and crustal

movements of the western Mediterranean area.

|

|

[link_eng.html] |